28 enero 2021 Internacional

Corona pandemic shows many that states are poorly prepared

Declining growth, high debt levels, sustainability setbacks, a rising risk of poverty, democracy under pressure and dwindling reform capacity. An international examination of governance by the Bertelsmann Stiftung shows that far too many EU and OECD countries were poorly prepared as the pandemic broke out in early 2020.

Gütersloh (Germany), 26 January 2021. Was everything really better before? This certainly isn’t true with regard to the time just before the coronavirus, as an analysis of policymaking by Christof Schiller und Thorsten Hellmann shows. The Bertelsmann Stiftung governance experts studied 41 EU and OECD countries to see how well prepared they were when the pandemic broke out. The findings are alarming: Before the coronavirus crisis, many states had failed to craft convincing responses to the challenges of digital transformation, the scarcity of natural resources, climate change, social inequality and increasing political polarization. The data used for this analysis were drawn from the Sustainable Governance Indicators (SGI), which produces yearly assessments regarding the sustainability of political outcomes, the robustness of democratic standards and the quality of governance in developed countries on the basis of three indices, 157 indicators and detailed country reports.

“Countries remain at vastly disparate points along their journey towards sustainable and forward-looking policymaking,” said SGI project head and study coauthor Schiller. The backlog of reforms has increased since the economic and financial crisis of 2009, in some cases dramatically. “In the absence of decisive joint countermeasures, the COVID-19 crisis will deepen these disparities further,” Schiller warned.

Major differences in developed countries’ sustainability records

Even before the pandemic, growth had slowed significantly in many countries. Between 2009 and 2019, Ireland still performed best, with a real economic growth rate averaging 5.3%. Germany managed an average rate of 1.3%. In Italy, Greece, Finland and Cyprus, per capita GDP had yet to return to its 2008 precrisis levels by 2019. Before the onset of the COVID-19 crisis, only a few states had been able to successfully reconcile dynamic economic performance with more effective natural-resource conservation and a well-developed research and innovation policy.

In addition, many countries saw an inequitable distribution of the benefits of recovery, despite employment growth. For example, in about half of the 41 developed countries assessed, the risk of poverty just before the coronavirus crisis was higher than it had been even at the height of the economic and financial crisis in 2013. The coronavirus-related increase in unemployment rates will increase the risk of poverty for young people, women and the self-employed. “The developed countries should do everything in their power to ensure financial support for those most affected by the crisis. Otherwise, there is a risk that the employment crisis will turn into a social crisis,” warned Hellmann, the study’s other coauthor.

In a worrying sign for successful crisis management, the quality of education has deteriorated in many places. Moreover, the already unequal distribution of educational opportunities between countries threatens to worsen further. Education systems showed very different degrees of preparation with regard to using digital distance-learning mechanisms to compensate for canceled classes and school closures.

State reform capacities vary widely

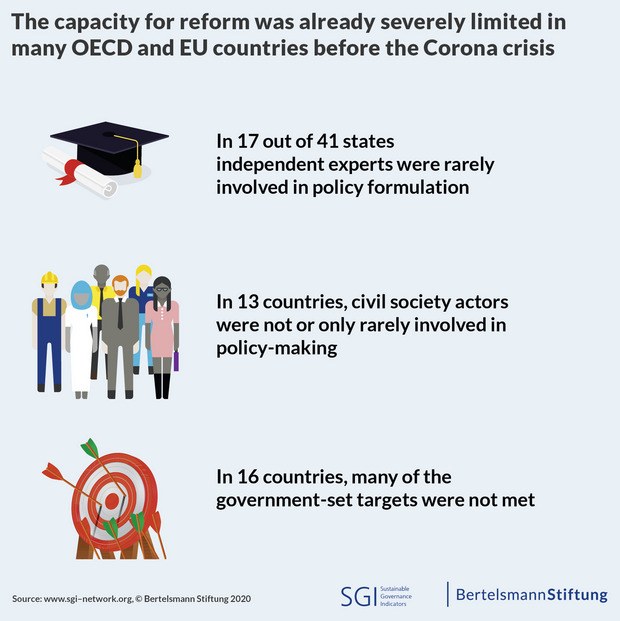

The fact that governments’ steering capabilities have further diminished in many places is also discouraging. A majority of 26 countries have seen stagnation or further deterioration in this area. This is exemplified by the capacity to consider expert advice in the early stages of policy formulation. In 17 of the 41 countries, independent experts were either never or only rarely involved in such policy processes over the course of 2019.

The participation of relevant societal groups will also be a key factor in determining the quality of the crisis response that now lies ahead. However, in 13 countries, this form of inclusive governance played virtually no role even before the crisis. Worryingly, governments’ capacity to achieve their own goals has also declined in many places since 2013. In more than half of the countries surveyed, for example, there was a deterioration with regard to the achievement of goals.

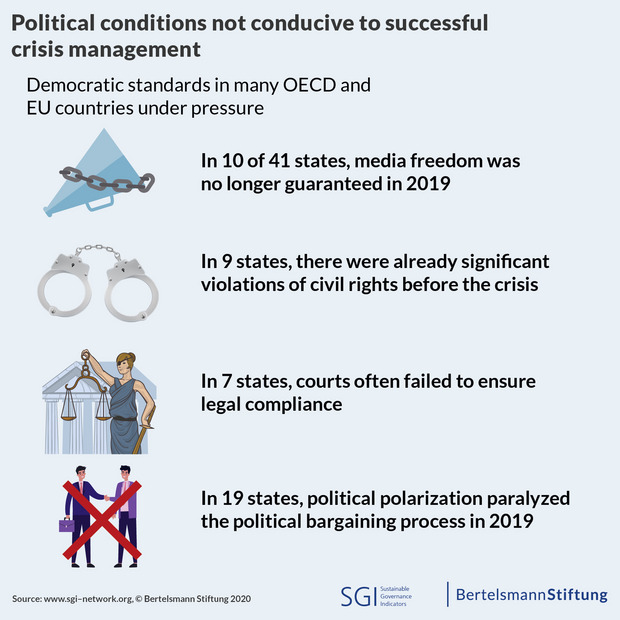

An economic and social crisis is seen as a dangerous breeding ground for the rise of antidemocrats. Even before the pandemic, it was clear that the EU and OECD countries are by no means immune to the erosion of democratic standards. Democratic standards have deteriorated in 24 of the 41 countries surveyed in comparison to 2013, the height of the negative economic and social effects of the economic and financial crisis. In Turkey, Hungary, Mexico, Romania and Poland, democratic norms and institutions such as a free press and an independent judiciary have already been severely compromised. In eight additional countries – Bulgaria, Japan, Croatia, the United States, Iceland, the Netherlands, Australia and Israel – democratic standards were already under severe pressure before the crisis.

In many countries, populists have additionally succeeded in deepening political and societal divides and shaking the population’s trust in evidence-based policies. In 19 of the 41 countries, the extent of political polarization was already a significant obstacle to the development of sustainable policies even before the crisis. This has had a disastrous impact during the crisis. “Without broad societal support and trust in the government’s crisis response, even the best ideas will lack the necessary traction to gain acceptance in practice,” the authors warn.